Magic: a Dilemma for Christianity

Where and why the two butt heads

3. Magic: a dilemma for Christianity

While it is clear that paganism disappeared, it is equally clear that Magic did not vanish. As a result, the issue of magic always posed a dilemma for the Church. The dilemma could not be solved by crushing Magic because belief in supernatural powers was an integral part of the culture into which Christianity was born. Indeed, Magic was an integral part of Christianity itself. The old and new testaments are full of demons and angels, prophesies and miracles.

The reality of demons and their efficacy could not be dismissed since they are discussed in the bible. Divination by astrology could not be dismissed without disallowing the Magi that saw the star announcing the birth of Christ. Foretelling the future could not be dismissed without discounting the Old Testament prophets. Miraculous cures are documented throughout the New Testament.

Magic was also an integral part of the Judeo-Christian mystical tradition. The early Jewish apocalyses, such as 2Enoch, make revelation of the secrets of nature an integral part of the mystical experience (Himmelfarb 1993). Initiation, magical passwords, and participation in angelic rituals were an important part of this literature. Christianity from the time of Origen maintained that both scripture and nature contained a level of meaning that was secret or occult or mystical (Idel 1995). Magic with Divine authority was part and parcel of the highest levels of Christian religious experience.

Since the non-material world was very real for the Christian, spiritual activity in the form of magic and miracles must necessarily also be real. The tricky bit is distinguishing the blessed from the nasty. This "tricky bit" was a constant dilemma for the Church, leading to decision that appear inconsistent to us today.

The dilemma is examplified of the Benandanti. The Benandanti were late medieval Christian shaman or good witches in northeastern Italy (Klaniczay 1990). Their role was to ward off evil from the village by battling demons. They believed that their mission and their ability were God-given. The Inquisitors were baffled! It was not clear that these women were heretics or under the influence of demons. The Benandanti were released with light penances. A similar phenomenon occurred in Yugoslavia and Hungry where the Kresnik were good witches who waged spirit battles with evil witches (Klaniczay 1990). The point is that, within a culture that believed in magic and within a religion that authorized exorcisms of demons, the Inquisitors had to fall back on authority: "We didn't authorize it, so stop." Not a very compelling argument! The good witches could be accused of ignorance, but not of evil.

A second way of perceiving the dilemma is how Magic was handled in official documents. In the early Church, relatively innocent forms of magic, such as divination, were dismissed with lenient penances. Indeed, Augustine felt that casting lots to find the verse of scripture that indicated one's fortune was less objectionable than other forms. The Decretum of Burchard of Worms (1008/12) is also lenient in punishments for Magic (Flint 1991). Indeed, a balanced look at legal restrictions during the late Middle Ages shows that Magic is not prominent (Peters 2002). Magic largely remains in the background with moral and spiritual life taking prominence. Magic was more associated with ignorance and only became of importance when associated with heresy or performing evil deeds.

Finally, the dilemma that Magic posed for the Church can be seen in the inconsistency of statements made by authorities and prominent theologians. Thomas Aquinas condemned almost all divination as demonic. However, he admits that some forms of divination have a natural basis and are permissible. Thus, it is possible to forecast the future by interpreting dreams! He declares alchemy to be a true art and astrology to be a licit science (Thorndike 1923). The same attitude toward astrology and alchemy as science was reflected in the writings of Duns Scotus (d. 1308) (Thorndike 1934).

Augustinus Triumphus (1243-1328) presented a treatise on astrology to Pope Clement V. The Pope's acceptance indicates that the work was an inoffensive or even orthodox statement. The work contains the interesting idea that NOT using legitimate natural magic might be evil: "An astrologer would sin if he allowed a client to sail when the sun was in an unfavorable sign which he believed portended a perilous storm. Similarly a physician would sin who ordered phlebotomy when the moon was unfavorable thereto." (Thorndike 1934).

Arnald of Villanova (late 13th-early 14th century) was a physician and alchemist. He wrote on the use of astrological images as an aspect of natural science. He condemned magic through the invocation of demons but held that natural objects have occult properties due to their association with stars (Thorndike 1923). What others condemned as magic, he praised as science.

Peter of Albano (early 14th century) was one of the last medieval scientist/magician writers. Peter considered astrology as a science and used astrological image magic and Pythagorean numerology in his medical writings (Thorndike 1923). Interestingly, Peter is quoted favorably by Michael Savanarola, grandfather of the reformer, who apparently had a favorable opinion of magic (Thorndike 1923).

While Augustinus, Arnald and Peter were never censured for their writings, Cecco d'Ascoli did not fare as well. The court astrologer at Florence was condemned by the Inquisition and burned in Florence in 1327 (Thorndike 1923). His condemnation is sometimes cited as proof of the Church's monolithic attitude toward magic. However, he was not condemned because he was a magician but because of a theological error: he maintained that the star of Bethlehem was not a miracle but a natural event (Thorndike 1934). That the condemnation was not a censure of astrology is also indicated by the fact that Niccolo di Paganica published a work on medical astrology in 1330, just 3 years after Cecco d'Ascoli was burned (Thorndike 1934).

Marianus Sozzini of Sienna (1401-1467) was a lawyer of Church Canon law at Padua and Sienna. His writings are a good clue to what was actually felt to be against Church law. He emphasizes divination by the casting of lots, but also deals with the occult and magic arts. He doesn't condemn divination but thinks it is not a good idea because it goes beyond reason and faith, the gifts given by God to humans to determine how to live. But, at the same time, astrology is approved because it uses human reason and science/mathematics. As long as astrology doesn't maintain that man is forced by stars, in violation of free will, it is licit. He also approves of wearing a verse from gospel around one's neck as protection against fever. Yule log ceremonies are okay. Even though they preserve a pagan custom, they can be used by Christians to celebrate the coming of light with the birth of Jesus. Ringing church bells against hail or plague is not against Church law. He also approved the wearing of gems since they have great occult powers (Thorndike 1934).

During the pontificate of John XXII (1316-1334) several archbishops and clerics were convicted of using poisons and wax figures for evil purposes. In 1320, the Viscountis were accused of trying to kill the pope by burning an effigy. In 1323, a general chapter of the Dominicans pronounced excommunication on any practicing alchemy. At the same time, the pope had little objection to astrology (Thorndike 1934).

Sometimes, the inconsistencies strike one as humorous. Thus, one may not use soil that a person has stepped on to make potions, but soil from a saint's footprint can affect miraculous cures (Jolly 2002)! One medieval writer condemned the use of incantations in collecting medicinal herbs but he granted that prayers thanking God for the herbs were appropriate (Jolly 2002)! One even finds blessings for herbs in liturgical manuals. Similarly, treatment of a physical ailment might include incantations potentially offensive to the Church while, at the same time, invoking the miraculous powers of a saint whose cult is promoted by the Church (Jolly 2002). The Council of Pisa in 1409 condemned the Pope for employing diviners but allowed "legitimate knowledge" of astrology (Peters 1978).

Petrus Mamoris of Limoges was a professor of theology. His writings condemn magicians as charlatans, "selling wind in a pillbox to sailors" (Thorndike 1934). He vehemently protests that demons cannot be compelled to do the will of the magician by the use of stones or herbs. But then admits that demons CAN be repulsed by these same objects (Thorndike 1934)!

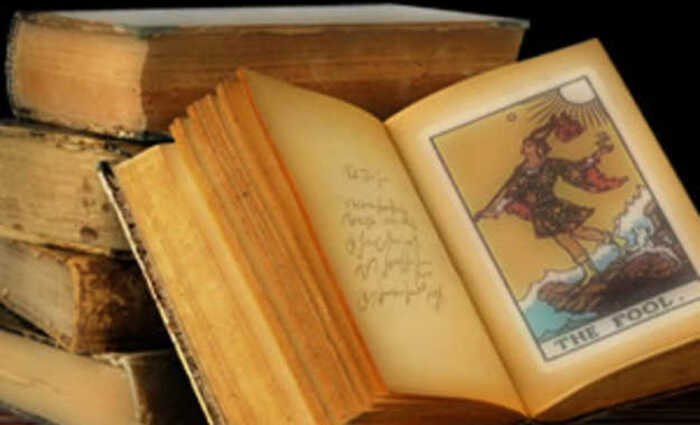

The point of these anecdotes is that magic posed a dilemma for the Church. The solutions posed by the best minds of the Middle Ages seem inconsistent and contradictory in the 21st century. Clearly, the early 15th century didn't think about magic in the same way we do today. Coming to understand how the early Tarot card-players thought about magic and its possible connection to the cards is the point of these essays. And the first point that I want to drive home is that to arrive at that understanding, the 21st century reader must step away from modern concepts of the esoteric, the occult, and the magical. In the 15th century, Italy was Christian and everyone believed in magic. But they clearly didn't define magic in the way that we do.